- About

- Methods & Sources

- Community

Friday, February 24, 2023 - 11:12

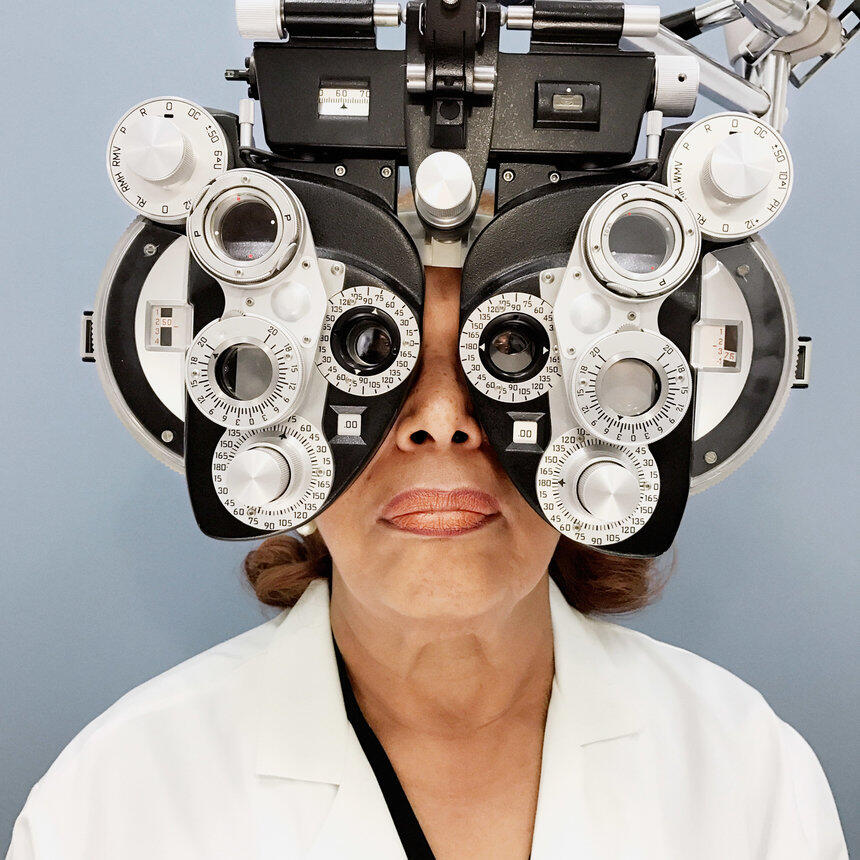

Spotlight on Patricia Bath

In 1986, Patricia Bath filed for a medical patent for a novel method to remove eye cataracts. Bath was the first African American female physician to acquire a patent. Her patent has been referenced over 100 times since its filing and has been cited as recently as February 2022 by Gregg Scheller and Matthew N. Zeid in their steerable laser probe patent.

The patent data alone will not tell you that Bath was the first African American female physician to acquire a patent. The race of inventors, like gender, is not part of any data collected by the USPTO and would require attribution algorithms similar to the gender attribution currently conducted by the PatentsView team.

Dig Deeper into Patent Data

PatentsView provides an opportunity to look at women in innovation more broadly. With PatentsView’s bulk downloads data, you can now query the data to see counts and types of inventions by male and female inventors in the aggregate.

Last Fall, PatentsView hosted a symposium on the attribution of demographic information to inventors listed on patents with the USPTO’s Office of the Chief Economist. This symposium included updates on predicting gender and race using artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches, as well as insights on economic implications of these predictions to innovation policy.

These methods show how researchers can dig deeper into the data to reveal trends and opportunity gaps for inventors and entrepreneurs.

Looking Toward the Future

The breadth of PatentsView’s mission has evolved as the project matures. Beginning in 2012 with an endeavor to connect and show the work of unique inventors over time and place, the PatentsView project has expanded the scope of its connection and discernment efforts to the assignees, locations, attorneys, and gender of inventors involved in patenting the country’s latest innovations.

With the pursuit of disambiguation algorithms becoming more advanced in what they can identify from publicly available information on inventors and their patents, there is a need to consider the methods and implications for this line of inquiry.

For gender attribution, the algorithm assigns the likelihood of the inventor being “male” based on the person’s name and their location in the world. The other options for the inventor are “not male,” aka female in this dichotomous view of gender, and “unassignable,” meaning that the algorithm was not able to confidently assign male or not-male to the inventor.

A similar method could be applied to the likelihood of an inventor being of a certain race, nationality, or ethnicity. There are a variety of algorithms available using numerous different methodologies and each has unique advantages and disadvantages in terms of accuracy, expense, and time.

What do you think about the future of race attribution in innovation? Tell us in the forum.